Creating a Language: A Simple Guide

The basic structural elements you need to create a language.

For the last couple of weeks I’ve been struggling a bit with coming up with topics to slap on here. But then I thought, “Adam, just give the people what they want!”

I got an interesting question here on Substack a couple of days ago.

How does one go about creating a language?

First of all, I’m not an expert on this. This question was a result of a discussion where I mentioned that I was working on an etymological analysis of Tolkien’s works. But I thought, what the heck, sounds like an interesting topic for my weekly article – so I’ll give it a go.

Nonetheless, this article doesn’t aim to be an exhaustive exploration of the topic – that would take far longer than a week.

Of course, I wouldn’t have a clue where to start or what to say, except for: the only way to create a language is to analyze and de-construct the languages we already know, find patterns and rules, and apply them to our fictional language. And, hopefully, it works.

(I might also just randomly come up with names for objects and things around me and try to make sense of it all on the fly. I actually wonder if that could work… I’d probably get confused and lost fairly quickly. Just imagine a certain situation within said culture and try to think how the people would describe it – given the setting, surroundings, history, environment, political structures etc.)

Piece of cake…

But, to gain better grasp of the topic, I did a bit of research and decided to write about what I learned. In this respect, I’ve found David Peterson’s talks extremely helpful. I’ll provide all the links at the end of the article; he also wrote a book on conlang (created languages) – but I haven’t had the time to rip through it this week, so I’ll probably do a second part delineating some of the ideas therein…

Where do you even start…?

The first thing you need to know when creating a language is who the speakers are. What is their culture like, their history, customs, etc. This could be, however, considered as world building – but language creation is an inherent part of worldbuilding in many fantasy and sci-fi franchises.

Then you also need to think about the WHY:

Why do you need to create a language in the first place?

So, the place to start would be:

What’s the purpose of your language?

Is it trade? Art? Daily communication? Academics? Science?

Who are the speakers? What’s their cultural background? What are their customs…?

After you find answers to your questions… Just stick to it. Don’t alter your principles as you go. Of course, natural languages evolve and change all the time, but this isn’t possible when you’re creating an “artificial” language.

(Unless your created language somehow becomes a part of everyday life in which case I imagine that some development would be possible, or almost inevitable.)

You should also think about whether your language is synthetic, agglutinative or inflectional. This will dictate the complexity of your words: particularly, whether there are compound words or not. Tolkien actually preferred the agglutinative aspect for his languages – as in Finnish, which often uses suffixes to change the meaning of the word or give it different grammatical categories. Synthetic languages need separate words to express grammatical categories.

Culture and Language

With customs and culture come also, for example, idioms – these, if done right, could give your language a sense of reality, history and depth. If we look at Dothraki from the Game of Thrones, I’d imagine they have a plenty of horse-centered idioms and expressions, as they consider themselves “horse-lords” and their culture puts considerable emphasis on these animals.

You can base your language on a culture centered around virtually anything you like – trees, books, horses etc. The nature of your culture will then dictate the linguistic variety and etymology.

Tolkien said:

“Mythology is language, and language is mythology. The mind, and the tongue, and the tale are coeval.”

He believed that the words and their sounds should reflect their meaning and the cultural characteristics of the speakers.

Just to illustrate, here are examples how the cultural and historical background might influence your language creation process.

Example A: English and Slovak

In Slovak, there is a lot more limited linguistic variety of adjectives related to feelings when compared to English – this can be due to the Slovak culture being much more reserved and less “emotional” than the English, so naturally, the English would need more adjectives to describe a wider emotional range. This limited emotional scope could be the result of the Slovak nation being historically poor; while the English have been historically rather a rich nation. Naturally, people whose objective is simply to survive will show a lot less interest in their emotions than people who have their basic needs covered – and therefrom stems the difference in linguistic variety/simplicity between languages.

Example B: Orcish/Black Speech and Elvish

If we look at Tolkien’s created languages, we’d find the Black Speech (Orcish) and Elvish languages.

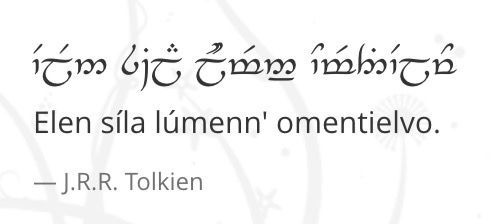

Elvish languages reflect the contemplative, almost artistic grace, and culturally developed nature of Elves. Take the famous sentence: Elen síla lúmenn’ omentielvo (Let the stars shine on the hour of our meeting). This is considered a basic greeting in the language – it’s long and elegant, almost like a song or a poem: suggesting that the culture is more developed, sophisticated and the speakers have enough time to use this greeting. There are other things we could derive from that, such as they probably have longer life spans, they’re more connected with their past etc.

The Orcs, however, being an industrious, warmongering sort of folk who would probably prioritise efficiency over elegance and aesthetics, might use fewer words – maybe only short sounds, with some guttural and rough phonemes (take, for example, the word nazg, which means “ring”).

The process of language creation

Peterson says you can start by simply opening a dictionary and coining a new term for every single word. But I have a feeling that sooner or later, you’d realize that you might need a system – sort of like natural languageshave.

Natural languages reflect the culture in which they’ve been developing, as well as the development of the said culture. The “system” is evolving naturally and synchronously. The problem here is, we don’t have thousands of years of development and cultural history at our disposal for something we’re creating right now… So, we just need to make the language up – probably by drawing inspiration from some real-world elements, history and etymology.

Example

The word “might” – which today is used to indicate possibility, used to have a meaning closer to “having the ability to do something”. Introducing such connections in a fictional language begs for the necessity to understand causal relationships between actions. For example, our fictional word for “fail” could be etymologically related to the fictional word for “try” – well, because if you try, it almost invariably implies that you must fail. Otherwise, you would just “do”. These fictional words for “try” and “fail” could then share a linguistic root or a morpheme. And so on and so forth… The derived words then reflect the type of culture they’re being used in. For example, tribalist (collectivist) cultures which are more oriented on family might draw linguistic or semantic (morphologic) similarities between the words for “home” and “family”, etc.

BUT!

To make the process of language creation more efficient, you’ll need some tools.

This article ponders some basic structural elements you might need to start creating a language “from scratch”.

Professor of linguistics from MIT Norvin Richards says:

“As students learn how various languages form tenses, plurals, and kinship terms, as well as how they borrow and shape words taken from other languages, they are gaining the tools to create entirely new languages… You present students with a little menu of the kinds of sounds you can make, and the students are picking and choosing and sometimes picking something that no language does.”

So, the goal is to present you with such a menu – and if you like any of the items, feel free to dive deeper and explore; there is a lot more to language creation than is explored here…

Basic structural elements of a language

Language is built on sounds. So first we need a sound system – the phonology.

Basically, what do our letters (consonants and vowels) sound like?

Second, you should also make sure you get your orthography straight – that is, what letters are you going to use? And, ideally, what will the “romanization” look like?

For example, Tolkien used Tengwar script for his Elvish; and all Elvish words can be re-written (phonetically) in the Roman alphabet.

Consonants and vowels

Once you have your letters, you can start choosing sounds for vowels and consonants – or you can do this simultaneously.

You need both consonants and vowels to put your words together. Otherwise, your language might be pretty hard to pronounce, and fall apart.

The most important goal is for the language to be functional – and functioning. So that means, I guess, that you are able to convey what you need in an efficient and clear way to fellow speakers – you must be able to pronounce it.

You can have long and short vowels: a, e, i, o, u OR [a:], [e:], [i:], [o:], [u:].

Most Slavic language speakers are familiar with the long sounds. Anglo-Saxon cultures might be a bit lost, but it’s pretty easy – it’s basically saying the same sound but holding it for a bit longer. So the long “a” is like “aaah”; long “i” is “eeeh”; long “o” is “awwwh” and so on.

Consonants and vowels then naturally group and form syllables. Usually, consonants and vowels within syllables/words would alternate; but some languages, like Georgian, don’t really respect this “rule”.

This one’s up to you – after all, it’s your language!

Example: Khuzdûl

A good example of a fictional language where we can really see how this works is the Khuzdûl language of Tolkien’s dwarves. It’s built around tri-consonantal root systems with vowels popped in between them – just like the Arabic language, for example, which uses the consonants k-t-b as roots (always in the same order within the words).

Dwarvish uses words such as: Khuzdûl and Khazad – root k-z-d… Again, the consonants are always in the same order. There are many other words that demonstrate this, which I will dedicate a separate post to.

This leads us to the fact that some languages “allow” certain groups of letters to stand together, while others don’t. In English, we would find the combination “pl” (plural), but we wouldn’t find “tl” (not counting the -ttle ending, like in cattle, kettle). I think it’s sort of the same in Spanish. In Slovak, we would find both.

Peterson seems to put a lot of emphasis on the allowed combinations of consonants and vowels (sounds) – so if you’re thinking about creating a language, this seems like a good place to start.

Combining consonants without vowels

In Swahili, there is, for example, a word “mtoto” (child). The letter “m” should carry emphasis, so they put a dot beneath it to make that clear. Otherwise, you might end up with a pronunciation closer to “toto” or “em-toto” (neither is correct). This only goes to show you can also employ markings (extra-linguistic elements) to make the pronunciation of your words clear.

Plural nouns

Vowels and consonants form syllables and syllables form words. These can be, for example, nouns – and they come in singular and plural forms.

We can form the plurals the “English way”, where we add an -s at the end (most of the time). Or we can change the word a bit (mouse changes to mice) – Tolkien’s languages often use this type of plural creation, where “amon” for “a hill” becomes “emyn” for “mountains”; or we have a noun that reflects singular and plural in the same form (it’s like if your order two Guinness, not two Guinnesses).

There are also some languages that create plurals by duplication of words, like in Indonesian: orang and orang-orang (person changes to people).

As far as I’ve come to see, one language usually operates chiefly with a single plural formation concept – and the rest is labelled “irregular”. If you devise a different plural-formation strategy for each word, your language will probably become unreasonably complicated.

Gender

You can also assign gender to your nouns. In Slovak, we know three genders (as is the case in German, too, for example) – masculine, feminine and neuter (neither). This is not true for all cultures or languages, however. As David mentions, Swahili distinguishes between humans, big things, small things, dangerous/not dangerous etc., without any gender labels.

So, to give you a better idea of how this works, and how gender can impact the structure of your language (mostly with respect to adjectives):

Let’s take three words – book, tree, name. Book, in Slovak, is feminine (she). Tree is masculine (he). Name is neuter (it). This is important because gender is then reflected in other words that modify the respective nouns, like, for example, adjectives – this reflection is mainly realized by the use of different suffixes.

Spanish probably works better to demonstrate the noun-adjective gender agreement:

Libro pequeño – “libro” (book) is masculine, so the adjective takes a masculine ending, in case of Spanish, it’s “-o”

Cara bonita – “cara” (face) is feminine, so the adjective takes a feminine ending, in case of Spanish, it’s “-a”

The ending for each gender can be whatever you like it to be; but again, in order for this to work, you need to devise a consistent system that makes it clear that “this suffix refers to this gender”, and it’s going to be reflected in the noun-adjective structure, or any other structure you deem appropriate (it can also be noun-verb structure).

“Gender” in the context of language doesn’t need to be only tied to sex. It can refer to certain attributes, such as whether the noun is: large/small, living/thing, long/short, etc.

This is entirely up to you when creating a language – and, again, depends on the type of culture or society you have in mind. You’ll probably base your “gender” system on something that’s important to distinguish in the given culture (it can be based on elements, for example). Gender in this sense almost becomes more of a “class” – such as we know it from video games, where it also could be called a “race”.

Gender can also influence semantics of a language, so in some cases we will have the same word morphologically, but the gender (in this case in the form of an article) which we assign to it changes its meaning. This happens with a couple of words in Spanish, for example:

el capital – investment, money; la capital – capital city

el coma – coma; la coma – comma

There is more of them in Spanish, but for the sake of brevity and illustration, this will do. Having gender tied to your nouns is optional; as we can see in the case of English, there basically are genders, but they are not reflected in the grammatical structures. In Slovak, there are genders, and they are also reflected in the structures (same with Czech, German etc.). Gender can add an interesting dimension to your language, but it can also cause some confusion – so tread carefully!

Verbs

Verbs can either change based on the tense (present, past, future) or remain the same. This largely depends on the perception of time of the given culture you’re trying to create a language for.

So, a verb could either have the same form in the past tense or it would change (go – went). We can also add the future tense: In English we only add will or going to; but in Spanish we’d change the verb form:

hacer (do, infinitive) – hago (I do) – haré (I will do).

Past tense is basically the same principle – change of suffix…just in past forms.

There’s a lot more to verbs, but I’m doing an express crash course, so… no time for that. It only depends on whether you want your language to be “tense-agnostic” or you want the verbs to reflect when the action happens.

There would be also the aspect of whether the activity is in progress or done: so like “was opening” or “opened” – you can choose to reflect that in the verb forms, also by using some other auxiliary verbs (as is the case in English with the verb “to be”).

Modifiers

Modifiers modify nouns (shocking). They may come before or after a noun. For the sake of convenience, I’ll use Spanish and English as examples.

In English, we would say “black cat” – so the modifier stands before the noun. In Spanish, on the other hand, we would say “gato negro” (literally, cat black) – so the modifier comes after the noun.

In Spanish, the modifier changes according to the noun’s gender; in English it doesn’t change. You can choose either way of expression, but make sure it is always clear which noun is being modified by which modifier(adjective).

Pronouns

Pronouns probably have only one thing we need to consider, and that’s politeness. So in English, we don’t distinguish between the “informal you” and “formal you” (second person singular); whereas in other languages (Slavic languages, German, Spanish), we distinguish between the two. For example, Spanish uses tú for informal “you” – that’s how you would address a single (as in quantity) friend; usted for formal “you” – that’s how you would address a single stranger (again, quantity).

This has a lot to do with Hofstede’s cultural dimensions and power distance, but I’d dig myself in an even deeper hole by explaining that here… But feel free to rummage around those concepts.

Number and types of your pronouns depend on the genders you choose. Slovak has three genders(masculine, feminine, neuter) – and three pronouns reflecting that (ten, tá, to – him, her, it). You would then also have pronouns in the plural form (we, they…).

It also might be a good idea to decide whether you need the pronouns to be expressly stated every time, or if they can be omitted – and you’d use a suffix with the verb. For example, in English we always need to say “I speak” – saying just “Speak” doesn’t give us enough information, or the wrong information (might come across as imperative). In Spanish, we can say both “Yo hablo” and “Hablo” – it means the same thing, no confusion because we have the suffix -o there, inherently tied to first person singular.

Prepositions

Prepositions differ based on the type of language you choose to use. Agglutinative languages will use prepositions as parts of words – usually suffixes; this is the case of Finnish, for example:

talolla – can mean at the house, near the house, in the house.

Regardless of which it is, the preposition is already embedded in the word. If we asked an English speaker who knows nothing about Finnish whether there is a preposition in this phrase, they’d probably say no.

The prepositions are then more apparent in English or Spanish, for example:

En la casa – in the house

Or in German, where the different prepositions are also tied to different declensions of the definite and indefinite articles – but no details on that, I always get them confused.

I personally find the latter less confusing – where the preposition stands alone; but you should go with whatever makes more sense to you or seems more fun.

Word order

We touched upon this with the adjectives and modifiers that can either come before or after the noun. The basic word order in English is S-V-O (subject-verb-object):

I love cats.

In Japanese, this would be “I cats love.”

(This is actually the most common word order in the world. I wouldn’t have guessed it, to be honest.)

In Hawaiian, “Love I cats.”

There are languages where the word order would be “Love cats I” (Madagascar) – which is pretty funky, and I’m not going down that way.

For “Cat in the box”, the Japanese would say “In the box cat”.

Pick the order you want your sentence elements to be in and stick to it. It’ll give you a sense of structure. For starters, it’s probably best to pick one that is closer to your native tongue or the one you’re most proficient in.

Words and vocabulary

When creating words, you again need to first think about the culture they will be used in. If your culture is, say, like Dothraki, you probably won’t have a word for “phone”. But you will have tons of words for animals, food, meat or shelter. Klingon will probably have fewer words related to horses than Dothraki. And so on… Language, naturally, only arises and is formed by the material things and situations that can realistically transpire within said culture.

Then, if you create this sort of language and culture, you will probably have other fictional languages and cultures influencing it as well. Therein come to play loanwords and translations from other fictional languages, but that’s a whole other thing and level…

Example: Hand and Arm

Many languages don’t distinguish between the two, or, say, the words for both are the same. In Slovak, for example, the word “ruka” can mean both “hand” and “arm” – depending on the context. We do have a separate word for arm (I believe it’s “paža” – but it isn’t used frequently). Maybe it’s not even grammatically correct – my knowledge of Slovak is limited at times.

In English, the distinction is pretty simple – arm is the whole limb, while hand is the end of your arm you use for grabbing things, with fingers. It’s like leg and foot – this again, would be simply “noha” for both in Slovak. And there is a word just for the lower part – probably “šlapa” or “chodidlo” /khodidlo/ or more precisely in phonetic notation [xoɟɪdlo].

But in general discourse, we don’t make the distinction and let the context do the heavy lifting, so to speak.

So, make clear whether you want to distinguish between such words and concepts, and if so, how – whether the words will be morphologically related; to what extent, etc.

Example: Christmas

We know you can derive words from verbs: teach – teacher. You can also create words by synthesizing two concepts together, like the word Christmas (Christ + Mass).

An interesting phenomenon here is that the long schwa in “Mass” becomes short in Christmas, as does the “i”, which is a nice pattern we can notice in more words. By joining the two words together to create a new one; we also sort of “sacrifice” the sound “t”.

Sentences

Now that you have the words, the question is, how do you build a sentence? The example sentence we would try to translate into a new hypothetical language is:

Remember to wash your hands.

David talks about the word “remember” – how do we get to the word? It’s semantically related to “know”; it’s also somehow related to the past – because you can only remember something that happened in the past.

I’d also argue it’s tied to imagination – usually when you remember something, you imagine a moment, a time in the past. This also leads us to experience in some way.

The example is that we use “mati” for the word “know”; and “mamati” for remember. Putting the “ma” in front of the word should evoke something happening before or earlier in the past. Thus, “to know what was in the past” – to remember (mamati).

And you have a brand-new word, just like that! This kind of word formation is called derivation.

To give it the imperative mood, David uses a suffix: “-ya”. So “remember!” would then be “mamatiya!”. I’d probably opt for the Spanish way and subtract something from the infinitive (hacer – haz or in Slovak robiť – rob; we could do “mamat”).

As for wash, I can’t help but think of water and some connection with it; thus, we would first need the word for “water” and then somehow derive the verb from that, so it all makes sense. We could also say “warm water” – then we would have to derive the word “warm” from somewhere as well (Sun or a concept connected to heat, maybe energy).

Or we could first delineate concepts for hot and warm, and then go from there – add a suffix or prefix and make the words somehow related or connected. It all depends on the cultural context, origins and values, as previously mentioned.

The relationships between words and concepts we draw this way give the created language a sense of logic and reality.

There are, of course, numerous other aspects you need to consider, like numbers and letters, noun declensions with genders and the respective suffixes, tonality and stress of your words (could be used to alter semantics while morphology remains basically the same), etc.

A lot!

What should make language creation a bit easier is, according to David Peterson, studying unrelatedlanguages. So, instead of picking up Spanish, Italian and French, you could do Spanish, Japanese and Finnish – finding a lot more linguistic variety and thus, inspiration.

If you’re interested in more, check out David’s book: “The Art of Language Invention”, which deals with all the concepts above in lot more depth and detail, giving you the tools you need to come up with your dream, new constructed language – or a conlang.

Have fun!

References

https://news.mit.edu/2019/constructed-languages-linguistics-1218

https://youtube.com/@dedalvs?si=Ew-1mCfhzASP8jrH

Peterson, D. J. (2015). The art of Language invention: From Horse-Lords to Dark Elves, the words behind World-Building.

Fantastic read. At least for me, when watching a film or reading a book, I can always tell when the work has been put in to make a language feel alive, to give it grammar, a history etc, and when it is just a bunch of made-up nonsense.

Wow, very, very interesting. Can I use this to create at least one language for the story I am writing?